A Brief History

Drum machines had seen a huge surge in popularity during the late ’80s. Artists were starting to formulate custom loops and drum patterns, using samplers to take slices of an existing song and mould whole new tracks around them. However, many of these early drum machines were expensive and required an understanding of music production/theory. As a result, Akai spotted a gap in the market. They knew they could make something that was far more accessible and affordable.

Roger Linn had designed drum machines before. He was the brains behind previously successful products, including the LinnDrum and LM-1. They were first released in the early ’80s. These instruments used samples of authentic drums – as opposed to most other models of the period, which favoured a synth-based architecture. You can hear them on a tonne of Top 40 tracks from the same decade.

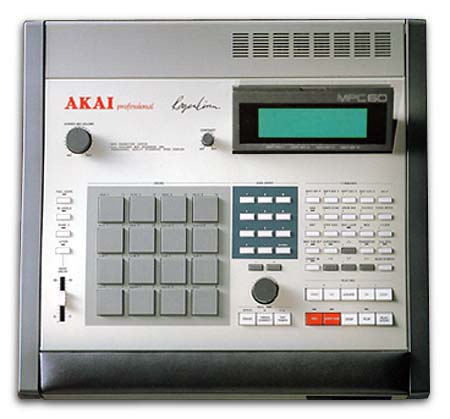

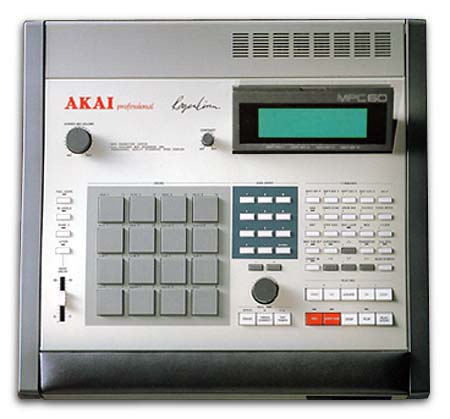

Headhunted by Akai, Linn was brought in to spearhead the brands’ assault on the drum machine world. This collaboration birthed the now iconic MPC 60 in 1988. It rivalled the preferred model of the day – the E-mu SP-1200 (which at the time, cost upwards of $10,000). However, this sampler couldn’t really compete with the MPC 60. With 13.1 seconds of total sampling time, a higher audio resolution, 128 pre-loaded sounds, and a cheaper price, the MPC 60 outgunned its rival in every single department. The fact that you could build and loop MIDI drum grooves or trigger sounds live only enhanced its versatility.

Users could now program drums to their hearts content. Beats could be quantized, or altered using the excellent built-in swing function. You didn’t have to necessarily imprison your recordings within a grid anymore. This all meant that grooves now had more of a human feel, contributing to realistic and better sounding drums. Everything became a lot less robotic and regimented.

Sampling was revolutionised too. Longer sample loops had been commonplace up until now, as there wasn’t a machine available that could easily cut up and order your samples. With the MPC 60, you could now store smaller, more manageable sections. These could then be sequenced and played back however you liked. Each could be assigned to a pad and triggered independently of one another.

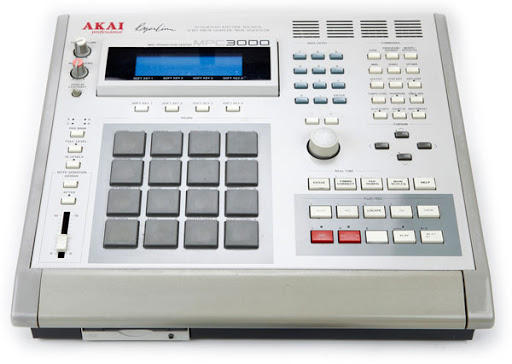

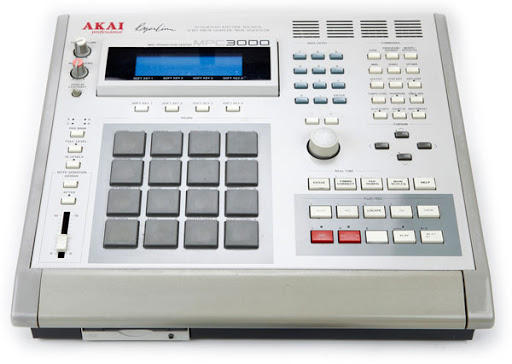

1993 saw further innovation with the release of the MPC 60’s successor: the MPC 3000. This built on the solid foundations of its predecessor, incorporating a wider suite of integrated effects, a longer sampling time, increased memory, improved MIDI compatibility and more notes per sequence. The MPC 3000 developed its very own legendary status within the hip-hop scene, just like the MPC 60 had done so before. This also proved to be Linn and Akai’s final project together, with the two parting ways soon after.

However, it was Linn’s software engineering and tactile, hands-on interface designs that continued to set the precedent for all future MPC models. Don’t fix what isn’t broken, eh? His creations not only influenced later Akai products, but a multitude of other pieces of hardware and software released by competing brands.

Akai pressed on, continuing to develop the range of MPC’s further throughout the ’90s and ‘2000s. There were now far more options available to consumers than ever before. The drum machine world would never be the same again.

Key Models

Just what made some of the most well-known and beloved MPC’s tick? We take a look at some of the essential features……

MPC 60 (1988)

– 13.1 seconds of sampling time.

– 16 square, velocity sensitive pads.

– 16 voice polyphony.

– Four pad banks (With 64 voices per program).

– 750kB sampling memory.

– Integrated 3 1/2-inch floppy drive.

– In built tilting LCD screen.

– MIDI capabilities.

MPC 3000 (1993)

– Improved sample resolution (16-bit)

– 22 seconds of sampling time (upgradable to 3 minutes).

– More notes available within each sequence.

– Enhanced memory.

– 32 voice polyphony.

– A wider range of integrated effects and filters.

MPC 2000 (1997)

– No signature swing feature.

– Two MIDI outputs.

– 64 tracks available.

– 2MB of sample memory.

MPC 2000 XL (2000)

– Powerful built-in effects unit.

– Expandable output board (allowing for up to 8 MIDI outs).

– Four separate pad-bank keys.

– Storage space for up to 256 samples.

– Sounds could be changed to a different sampling rate or bit depth.

– Time stretching was added.

MPC 4000 (2002)

– Combined the functions of the 60, 3000 and 2000XL into one unit.

– High resolution 24-bit sampling.

– 512MB of memory available.

MPC 1000 (2005)

– 64 tracks.

– 16MB of sample memory.

– USB port and a built-in CompactFlash card reader.

– Two MIDI outputs/inputs.

– Integrated suite of effects.

– Analog outputs.

– Highly portable.

MPC 2500 (2005)

– 100,000 note, 64 track mixer.

– 64 assignable MIDI channels.

– USB port for computer connectivity.

– CompactFlash slot sample storage.

– Could be upgraded with a CD-R/DVD drive for burning/reading discs.

Who Has Used An Akai MPC?

It’s more like who HASN’T used an Akai MPC at this point. The instrument has found its way into not just countless records, but many aspects of popular music culture too.

– Classic hip-hop track ‘Regulate’ by Warren G (Ft. Nate Dogg) features a drum pattern programmed on an MPC 60.

– Big Boi from Outkast created some of the duo’s most recognisable grooves using an MPC.

– Mark Ronson is a huge advocate of the MPC; he even owns one with a custom paint job.

– Legendary producer DJ Shadow made use of an MPC 60 to craft his seminal debut album ‘Endtroducing’. The record was created entirely using samples.

– Dr. Dre used the MPC 3000 on both ‘The Chronic’ and ‘2001’ – with many stating that he used as many as five to achieve his desired sound.

– J Dilla (arguably one of the greatest beatmakers to ever live) used an MPC 3000 across the course of his entire career. His combination of soul loops, manually programmed drums, signature low-end textures and pitched/stretched samples resulted in a series of stunning soundscapes. Even as DAW’s became commonplace, J Dilla remained faithful to his MPC, incorporating it into his updated workflow.

– J Dilla’s very own limited edition MPC 3000 became so iconic, that it’s now part of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture’s collection.

Responses & Questions